Python算法设计篇(4) Chapter 4: Induction and Recursion and Reduction

You must never think of the whole street at once, understand? You must only concentrate on the next step, the next breath, the next stroke of the broom, and the next, and the next. Nothing else.

——Beppo Roadsweeper, in Momo by Michael Ende

注:本节中我给定下面三个重要词汇的中文翻译分别是:Induction(推导)、Recursion(递归)和Reduction(规约)

本节主要介绍算法设计的三个核心知识:Induction(推导)、Recursion(递归)和Reduction(规约),这是原书的重点和难点部分

正如标题所示,本节主要介绍下面三部分内容:

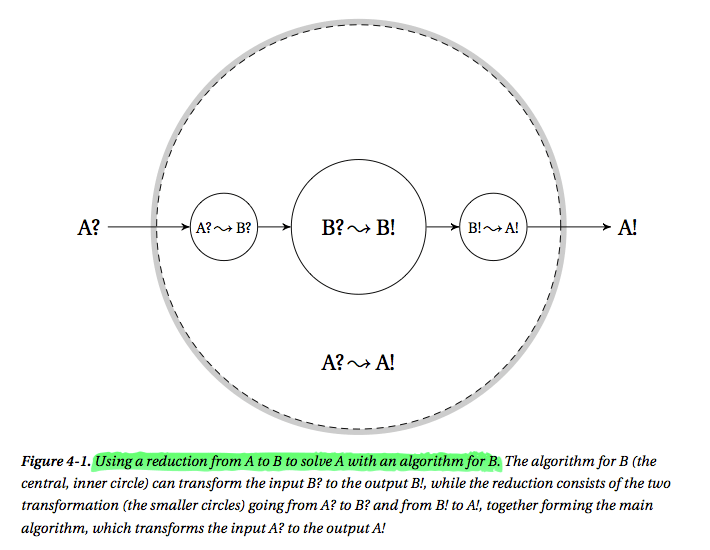

• Reduction means transforming one problem to another. We normally reduce an unknown problem to one we know how to solve. The reduction may involve transforming both the input (so it works with the new problem) and the output (so it’s valid for the original problem).

Reduction(规约)意味着对问题进行转换,例如将一个未知的问题转换成我们能够解决的问题,转换的过程可能涉及到对问题的输入输出的转换。[问题规约在证明一个问题是否是NP完全问题时经常用到,如果我们能够将一个问题规约成一个我们已知的NP完全问题的话,那么这个问题也是NP完全问题]

下面给幅图你就能够明白了,实际上很多时候我们遇到一个问题时都是找一个我们已知的类似的能够解决的问题,然后将这个新问题A规约到那个我们已知的问题B,中间经过一些输入输出的转换,我们就能够解决新问题A了。

• Induction (or, mathematical induction) is used to show that a statement is true for a large class of objects (often the natural numbers). We do this by first showing it to be true for a base case (such as the number 1) and then showing that it “carries over” from one object to the next (if it’s true for n –1, then it’s true for n).

Induction(推导)是一个数学意义上的推导,类似数学归纳法,主要是用来证明某个命题是正确的。首先我们证明对于基础情况(例如在k=1时)是正确的,然后证明该命题递推下去都是正确的(一般假设当k=n-1时是正确的,然后证明当k=n时也是正确的即可)

• Recursion is what happens when a function calls itself. Here we need to make sure the function works correctly for a (nonrecursive) base case and that it combines results from the recursive calls into a valid solution.

Recursion(递归)经常发生于一个函数调用自身的情况。递归函数说起来简单,但是实现不太容易,我们要确保对于基础情况(不递归的情况)能够正常工作,此外,对于递归情况能够将递归调用的结果组合起来得到一个有效的结果。

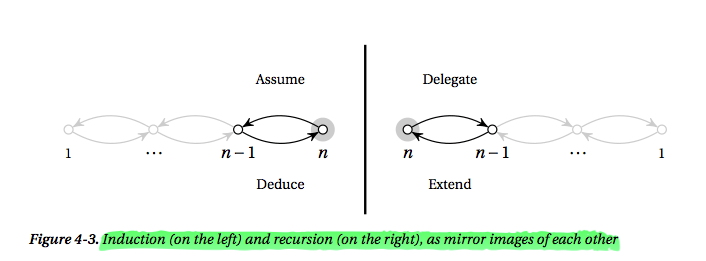

以上三个核心有很多相似点,比如它们都专注于求出目标解的某一步,我们只需要仔细思考这一步,剩下的就能够自动完成了。如果我们更加仔细地去理解它们,我们会发现,Induction(推导)和Recursion(递归)其实彼此相互对应,也就是说一个Induction能够写出一个相应的Recursion,而一个Recursion也正好对应着一个Induction式子,也可以换个方式理解,Induction是从n-1到n的推导,而Recursion是从n到n-1的递归(下面有附图可以帮助理解)。此外,Induction和Recursion其实都是某种Reduction,即Induction和Recursion的本质就是对问题进行规约!为了能够对问题使用Induction或者说Recursion,Reduction一般是将一个问题变成另一个只是规模减小了的相同问题。

你也许会觉得奇怪,不对啊,刚才不是说Reduction是将一个问题规约成另一个问题吗?现在怎么又说成是将一个问题变成另一个只是规模减小了的相同问题了?其实,Reduction是有两种的,上面的两种都是Reduction!还记得前面介绍过的递归树吗?那其实就是将规模较大的问题转换成几个规模较小的问题,而且问题的形式并没有改变,这就是一种Reduction。你可以理解这种情况下Reduction是降维的含义,也就类似机器学习中的Dimension Reduction,对高维数据进行降维了,问题保持不变。

These are two major variations of reductions: reducing to a different problem and reducing to a shrunken version of the same.

再看下下面这幅图理解Induction和Recursion之间的关系

[关于它们三个的关系的原文阐述:Induction and recursion are, in a sense, mirror images of one another, and both can be seen as examples of reduction. To use induction (or recursion), the reduction must (generally) be between instances of the same problem of different sizes. ]

[看了原书你会觉得,作者介绍算法的方式很特别,作者有提到他的灵感来自哪里:In fact, much of the material was inspired by Udi Manber’s wonderful paper “Using induction to design algorithms” from 1988 and his book from the following year, Introduction to Algorithms: A Creative Approach.]

也许你还感觉很晕,慢慢地看了后面的例子你就明白了。在介绍例子之前呢,先看下递归和迭代的异同,这个很重要,在后面介绍动态规划算法时我们还会反复提到它们的异同。

[Induction is what you use to show that recursion is correct, and recursion is a very direct way of implementing most inductive algorithm ideas. However, rewriting the algorithm to be iterative can avoid the overhead and limitations of recursive functions in most (nonfunctional) programming languages. ]

有了Induction和Recursion,我们很容易就可以将一个inductive idea采用递归(recursion)的方式实现,根据我们的编程经验(事实也是如此),任何一个递归方式的实现都可以改成非递归方式(即迭代方式)实现(反之亦然),而且非递归方式要好些,为什么呢?因为非递归版本相对来讲运行速度更快,因为没有用栈去实现,也避免了栈溢出的情况,python中对栈深度是有限制的。

举个例子,下面是一段遍历序列的代码,如果大小设置为100没有问题,如果设置为1000就会报RuntimeError的错误,提示超出了最大的递归深度。[当然,大家都不会像下面那样写代码对吧,这只是一个例子]

def trav(seq, i=0):

if i == len(seq): return

#print seq[i]

trav(seq, i + 1)

trav(range(1000)) # RuntimeError: maximum recursion depth exceeded

所以呢,很多时候虽然递归的思路更好想,代码也更好写,但是迭代的代码更加高效一些,在动态规划中还可以看到迭代版本还有其他的优点,当然,它还有些缺点,比如要考虑迭代的顺序,如果迫不及待想知道请移步阅读Python算法设计篇之动态规划,不过还是建议且听我慢慢道来

下面我们通过排序来梳理下我们前面介绍的三个核心内容

我们如何对排序问题进行reduce呢?很显然,有很多种方式,假如我们将原问题reduce成两个规模为原来一半的子问题,我们就得到了合并排序(这个我们以后还会详细介绍);假如我们每次只是reduce一个元素,比如假设前n-1个元素都排好序了,那么我们只需要将第n个元素插入到前面的序列即可,这样我们就得到了插入排序;再比如,假设我们找到其中最大的元素然后将它让在位置n上,一直这么下去我们就得到了选择排序;继续思考下去,假设我们找到某个元素(比如第k大的元素),然后将它放在位置k上,一直这么下去我们就得到了快速排序(这个我们以后还会详细介绍)。怎么样?我们前面学过的排序经过这么一些reduce基本上都很清晰了对吧?

下面通过代码来体会下插入排序和选择排序的两个不同版本

递归版本的插入排序

def ins_sort_rec(seq, i):

if i == 0: return # Base case -- do nothing

ins_sort_rec(seq, i - 1) # Sort 0..i-1

j = i # Start "walking" down

while j > 0 and seq[j - 1] > seq[j]: # Look for OK spot

seq[j - 1], seq[j] = seq[j], seq[j - 1] # Keep moving seq[j] down

j -= 1 # Decrement j

from random import randrange

seq = [randrange(1000) for i in range(100)]

ins_sort_rec(seq, len(seq)-1)

改成迭代版本的插入排序如下

def ins_sort(seq):

for i in range(1, len(seq)): # 0..i-1 sorted so far

j = i # Start "walking" down

while j > 0 and seq[j - 1] > seq[j]: # Look for OK spot

seq[j - 1], seq[j] = seq[j], seq[j - 1] # Keep moving seq[j] down

j -= 1 # Decrement j

seq2 = [randrange(1000) for i in range(100)]

ins_sort(seq2)

你会发现,两个版本差不多,但是递归版本中list的size不能太大,否则就会栈溢出,而迭代版本不会有问题,还有一个区别就是方法参数,一般来说递归版本的参数都会多些

递归版本和迭代版本的选择排序

def sel_sort_rec(seq, i):

if i == 0: return # Base case -- do nothing

max_j = i # Idx. of largest value so far

for j in range(i): # Look for a larger value

if seq[j] > seq[max_j]: max_j = j # Found one? Update max_j

seq[i], seq[max_j] = seq[max_j], seq[i] # Switch largest into place

sel_sort_rec(seq, i - 1) # Sort 0..i-1

seq = [randrange(1000) for i in range(100)]

sel_sort_rec(seq, len(seq)-1)

def sel_sort(seq):

for i in range(len(seq) - 1, 0, -1): # n..i+1 sorted so far

max_j = i # Idx. of largest value so far

for j in range(i): # Look for a larger value

if seq[j] > seq[max_j]: max_j = j # Found one? Update max_j

seq[i], seq[max_j] = seq[max_j], seq[i] # Switch largest into place

seq2 = [randrange(1000) for i in range(100)]

sel_sort(seq2)

下面我们来看个例子,这是一个经典的“名人问题”,我们要从人群中找到那个名人,所有人都认识名人,而名人则任何人都不认识。

[这个问题的一个变种就是从一系列有依赖关系的集合中找到那个依赖关系最开始的元素,比如多线程环境下的线程依赖问题,后面将要介绍的拓扑排序是解决这类问题更实际的解法。A more down-to-earth version of the same problem would be examining a set of dependencies and trying to find a place to start. For example, you might have threads in a multithreaded application waiting for each other, with even some cyclical dependencies (so-called deadlocks), and you’re looking for one thread that isn’t waiting for any of the others but that all of the others are dependent on. ]

在进一步分析之前我们可以发现,很显然,我们可以暴力求解下,G[u][v]为True表示 u 认识 v。

def naive_celeb(G):

n = len(G)

for u in range(n): # For every candidate...

for v in range(n): # For everyone else...

if u == v: continue # Same person? Skip.

if G[u][v]: break # Candidate knows other

if not G[v][u]: break # Other doesn't know candidate

else:

return u # No breaks? Celebrity!

return None # Couldn't find anyone

用下面代码进行测试,得到正确结果57

from random import *

n = 100

G = [[randrange(2) for i in range(n)] for i in range(n)]

c = 57 # For testing

for i in range(n):

G[i][c] = True

G[c][i] = False

print naive_celeb(G) #57

上面的暴力求解其实可以看做是一个reduce,每次reduce一个人,确定他是否是名人,显然这样做并不高效。那么,对于名人问题我们还可以怎么reduce呢?假设我们还是将规模为n的问题reduce成规模为n-1的问题,那么我们要找到一个非名人(u),也就是找到一个人(u),他要么认识其他某个人(v),要么某个人(v)不认识他,也就是说,对于任何G[u][v],如果G[u][v]为True,那么消去u;如果G[u][v]为False,那么消去v,这样就可以明显加快查找的速度!

基于上面的想法就有了下面的python实现,第二个for循环是用来验证我们得到的结果是否正确(因为如果我们保证有一个名人的话那么结果肯定正确,但是如果不能保证的话,那么结果就要进行验证)

def celeb(G):

n = len(G)

u, v = 0, 1 # The first two

for c in range(2, n + 1): # Others to check

if G[u][v]:

u = c # u knows v? Replace u

else:

v = c # Otherwise, replace v

if u == n:

c = v # u was replaced last; use v

else:

c = u # Otherwise, u is a candidate

for v in range(n): # For everyone else...

if c == v: continue # Same person? Skip.

if G[c][v]: break # Candidate knows other

if not G[v][c]: break # Other doesn't know candidate

else:

return c # No breaks? Celebrity!

return None # Couldn't find anyone

看起来还不错吧,我们将一个$O(n^2)$的暴力解法变成了一个$O(n)$的快速解法。

[看书看到这里时,我想起了另一个看起来很相似的问题,从n个元素中找出最大值和最小值。如果我们单独地来查找最大值和最小值,共需要(2n-2)次比较(也许你觉得还可以少几次,但都还是和2n差不多对吧),但是,如果我们成对来处理,首先比较第一个元素和第二个元素,较大的那个作为当前最大值,较小的那个作为当前最小值(如果n是奇数的话,为了方便可以直接令第一个元素既是最大值又是最小值),然后向后移动,每次取两个元素出来先比较,较小的那个去和当前最小值比较,较大的那个去和当前最大值比较,这样的策略至多需要 $3\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$ 次比较。两个问题虽然完全没关系,但是解决方式总有那么点千丝万缕有木有?]

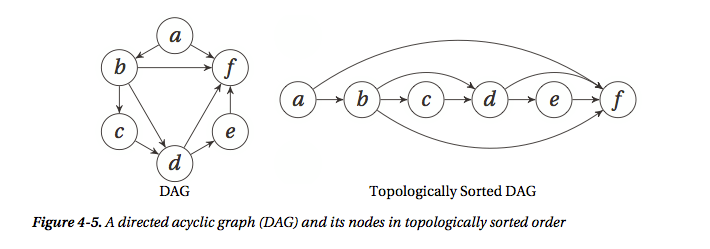

接下来我们看另一个更加重要的例子,拓扑排序,这是图中很重要的一个算法,在后面介绍到图算法的时候我们还会提到拓扑排序的另一个解法,它的应用范围也非常广,除了前面的依赖关系例子外,还有一个最突出的例子就是类Linux系统中软件的安装,每当我们在终端安装一个软件或者库时,它会自动检测它所依赖的那些部件(components)是否安装了,如果没有那么就先安装那些依赖项。此外,后面介绍到动态规划时有一个单源最短路径问题就利用了拓扑排序。

下图是一个有向无环图(DAG)和它对应的拓扑排序结果

拓扑排序这个问题怎么进行reduce呢?和前面一样,我们最直接的想法可能还是reduce one element,即去掉一个节点,先解决剩下的(n-1)个节点的拓扑排序问题,然后将这个去掉的节点插入到合适的位置,这个想法的实现非常类似前面的插入排序,插入的这个节点(也就是前面去掉的节点)的位置是在前面所有对它有依赖的节点之后。

def naive_topsort(G, S=None):

if S is None: S = set(G) # Default: All nodes

if len(S) == 1: return list(S) # Base case, single node

v = S.pop() # Reduction: Remove a node

seq = naive_topsort(G, S) # Recursion (assumption), n-1

min_i = 0

for i, u in enumerate(seq):

if v in G[u]: min_i = i + 1 # After all dependencies

seq.insert(min_i, v)

return seq

G = {'a': set('bf'), 'b': set('cdf'),'c': set('d'), 'd': set('ef'), 'e': set('f'), 'f': set()}

print naive_topsort(G) # ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

上面这个算法是平方时间的,还有没有其他的reduction策略呢?前面的解法类似插入排序,既然又是reduce一个元素,很显然我们可以试试类似选择排序的策略,也就是说,我们找到一个节点,然后把它放在第一个位置上(后面有道练习题思考如果是放在最后一个位置上怎么办),假设我们直接就是将这个节点去掉会怎样呢?如果剩下的图还是一个DAG的话我们就将原来的问题规约成了一个相似但是规模更小的问题对不对?但是问题是我们选择哪个节点会使得剩下的图还是一个DAG呢?很显然,如果一个节点的入度为0,也就是说没有任何其他的节点依赖于它,那么它肯定可以直接安全地删除掉对不对?!

基于上面的思路就有了下面的解法,每次从图中删除一个入度为0的节点

def topsort(G):

count = dict((u, 0) for u in G) # The in-degree for each node

for u in G:

for v in G[u]:

count[v] += 1 # Count every in-edge

Q = [u for u in G if count[u] == 0] # Valid initial nodes

S = [] # The result

while Q: # While we have start nodes...

u = Q.pop() # Pick one

S.append(u) # Use it as first of the rest

for v in G[u]:

count[v] -= 1 # "Uncount" its out-edges

if count[v] == 0: # New valid start nodes?

Q.append(v) # Deal with them next

return S

[扩展知识:有意思的是,拓扑排序还和Python Method Resolution Order 有关,也就是用来确定某个方法是应该调用该实例的还是该实例的父类的还是继续往上调用祖先类的对应方法。对于单继承的语言这个很容易,顺着继承链一直往上找就行了,但是对于Python这类多重继承的语言则不简单,它需要更加复杂的策略,Python中使用了C3 Method Resolution Order,我不懂,想要了解的可以查看 on python docs]

本章后面作者提到了一些其他的内容

1.Strong Assumptions

主要对于Induction,为了更加准确方便地从n-1递推到n,常常需要对问题做很强的假设。

2.Invariants and Correctness

循环不变式,这在算法导论上有详细介绍,循环不变式是用来证明某个算法是正确的一种方式,主要有下面三个步骤[这里和算法导论上介绍的不太一样,道理类似]:

(1). Use induction to show that it is, in fact, true after each iteration.

(2). Show that we’ll get the correct answer if the algorithm terminates.

(3). Show that the algorithm terminates.

3.Relaxation and Gradual Improvement

松弛技术是指某个算法使得当前得到的解有进一步的提升,越来越接近最优解(准确解),这个技术非常实用,每次松弛可以看作是向最终解前进了“一步”,我们的目标自然是希望松弛的次数越少越好,关键就是要确定松弛的顺序(好的松弛顺序可以让我们直接朝着最优解前进,缩短算法运行时间),后面要介绍的图中的Bellman-Ford算法、Dijkstra算法以及DAG图上的最短路径问题都是如此。

4.Reduction + Contraposition = Hardness Proof

规约是用于证明一个问题是否是一个很难的问题的好方式,假设我们能够将问题A规约至问题B,如果问题B很简单,那么问题A肯定也很简单。逆反一下我们就得到,如果问题A很难,那么问题B就也很难。比如,我们知道了哈密顿回路问题是NP完全问题,要证明哈密顿路径问题也是NP完全问题,就可以将哈密顿回路问题规约为哈密顿路径问题。

[这里作者并没有过多的提到问题A规约至问题B的复杂度,算法导论中有提到,作者可能隐藏了规约的复杂度不大的含义,比如说多项式时间内能够完成,也就是下面的fast readuction]

“fast + fast = fast.” 的含义是:fast readuction + fast solution to B = fast solution to A

两条重要的规约经验:

• If you can (easily) reduce A to B, then B is at least as hard as A.

• If you want to show that X is hard and you know that Y is hard, reduce Y to X.

5.Problem Solving Advice

作者提供的解决一个问题的建议:

(1)Make sure you really understand the problem.

搞明白你要解决的问题

What is the input? The output? What’s the precise relationship between the two? Try to represent the problem instances as familiar structures, such as sequences or graphs. A direct, brute-force solution can sometimes help clarify exactly what the problem is.

(2)Look for a reduction.

寻找一个规约方式

Can you transform the input so it works as input for another problem that you can solve? Can you transform the resulting output so that you can use it? Can you reduce an instance if size n to an instance of size k < n and extend the recursive solution (inductive hypothesis) back to n?

(3)Are there extra assumptions you can exploit?

还有其他的重要的假设条件吗,有时候我们如果只考虑该问题的特殊情况的话没准能够有所收获

Integers in a fixed value range can be sorted more efficiently than arbitrary values. Finding the shortest path in a DAG is easier than in an arbitrary graph, and using only non-negative edge weights is often easier than arbitrary edge weights.

问题4-18. 随机生成DAG图

Write a function for generating random DAGs. Write an automatic test that checks that topsort gives a valid orderings, using your DAG generator.

You could generate DAGs by, for example, randomly ordering the nodes, and add a random number of forward-pointing edges to each of them.

问题4-19. 修改拓扑排序

Redesign topsort so it selects the last node in each iteration, rather than the first.

This is quite similar to the original. You now have to maintain the out-degrees of the remaining nodes, and insert each node before the ones you have already found. (Remember not to insert anything in the beginning of a list, though; rather, append, and then reverse it at the end, to avoid a quadratic running time.)

[注意是使用append然后reverse,而不要使用insert]